|

Remembrance

- The Yorkshire Regiment, First World War The Fighting Cousins, - Frank & Samuel Maltby Close Window to return to main Page |

Chris Weekes, <weebex12@hotmail.com>, a great nephew of Frank Maltby, has researched the careers of Frank, - and his cousin Samuel, in the Yorkshire Regiment in the First World War. Frank lost his life in the conflict, though Samuel survided (after being made a Prisoner of War. The description of the background and careers of the two Maltby cousins, below, is a result of this research. THis account has been broken down into sequential "chapters", which can be selected from the links below.

8 THE 5th BATTALION RETREAT

The Arras campaign had removed both the Maltby cousins from active service. For those of the 5th Battalion who had survived, the remainder of 1917 was spent in and out of the front line trenches, in training and on working parties with the Royal Engineers. In mid October the Battalion was sent back to Flanders, firstly to Brandhoek ( Map ref J 2) and finally to Ypres. ( Map ref K 2).

According to the LONG LONG TRAIL website 64% of wounded men

returned to duty although normally to another fighting unit because their

place in their old unit had been filled by a replacement. It is probable

that Samuel R.D. Maltby 242471 returned to the 5th Battalion in early 1918

having been discharged from hospital to base camp at Etaples in December

1917. He had been away from active service for eight months. He was unusual

in that he returned to the same unit, A Company 5th Battalion Yorkshire

Regiment, back to the occupation of trenches in the Ypres salient the most

dangerous place on the Western front. The 5th Battalion war diary tells

us that at the end of February 1918 the Battalion was moved to Setgues NW

of St Omer (Map ref G 3) for training, until on 9th March they were sent

to Boves SE of Amiens ( Map ref H 8) again for training.

Intelligence was predicting a German offensive in the southern sector and

on 21st March 1918 the St Michael offensive commenced against General Gough’s

5th Army.

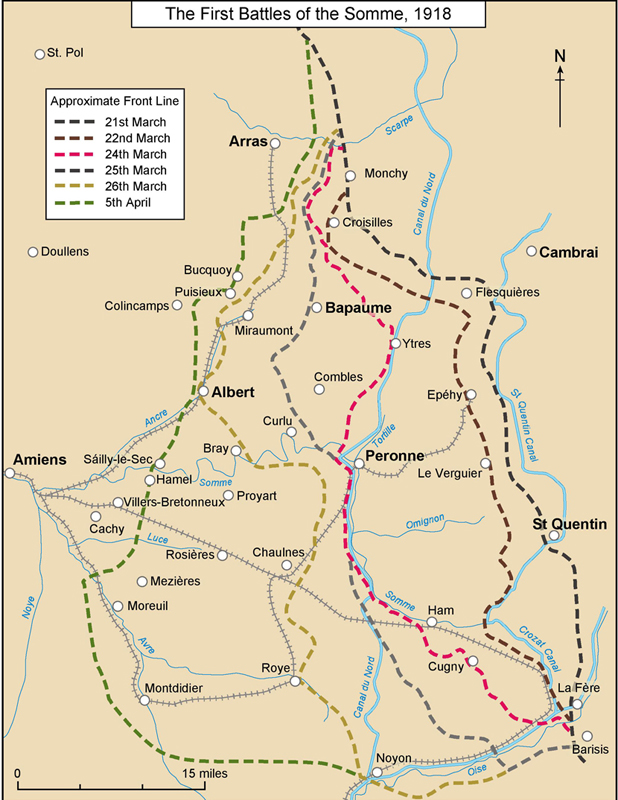

March 1918, German Offensive

The 50th Division was ordered east of Amiens to meet this German attack. The 5th Battalion war diary provides a detailed description of how the Battalion fought a rearguard action from 21st to 31st March resulting in a nine mile withdrawal from Hancourt (Map ref L 8) to Domart S.E. of Amiens (Map ref H 9). The retreat of the 5th Army is well documented in Peter Hart’s fantastically detailed book “1918 A VERY BRITISH VICTORY”.

The March defensive operations cost the 5th Battalion 372 casualties, including its commanding officer Lt .Col. Thomson who was wounded but still kept to his post. The regimental history by Wylly provides a graphic description of the Battalion’s involvement in trying to stem the hordes of German storm troopers. The 4th and 5th Battalions lost so many men and the whole thing became so chaotic that Battalion identities got lost such that groups of stragglers were grouped together to form the 150th Brigade Composite Battalion.

The 50th Division history points out that at the beginning of 1918 the BEF was exhausted, having had to take the brunt of the 1917 battles culminating in Passchendaele. The transfer of the German troops from the Eastern Front, with the collapse of Imperial Russia, gave the German High Command the resources to launch a series of blows against the British. The BEF had wind of this and had attempted to construct a new, in-depth defensive system that needed large numbers of the infantry to be engaged in working parties. This meant fewer men engaged in training in new battle tactics. With a lack of in-depth reserves, partly caused by Lloyd George’s refusal to release home based reserves, the British army was way below strength.

The Division history explains that the 150th Brigade arrived

at the front line on 22nd March 1918.

“The march from Brie to the Green line was a weary business for

already everyone was tired. Thick mist, darkness, heavy traffic on the main

road delayed progress.”

On 23rd March the withdrawal began:

“The 5th Battalion engaged with the enemy and fought a rearguard

action crossing the Somme canal at Brie.”

This withdrawal, officially known as the Battle of St. Quentin, was a tactical withdrawal across the river which was then expected to be defended against the Germans. However many individual diaries of the period show the soldiers’ dislike of withdrawal and the thoughts that they could have inflicted more damage on the enemy had they stood their ground. The 50th Division was relieved by the 8th Division on 23rd March, but on 24th the Germans crossed the Somme and the 150th Brigade was ordered to rush across country to bolster the defences. On 25th the Brigade was involved in some very hard fighting and had to withdraw even further and faster. As the situation became more chaotic the three Battalions of the 150th Brigade were formed into one composite battalion of 560 men of whom only 140 were from 5th Battalion including Samuel Maltby. The Division history makes this tribute:

“To the undying glory of the British soldier, let it be remembered of him that in the greatest battle the world has ever known, he carried himself with great honour and courage fighting the harder as the situation grew more desperate, often preferring death to surrender.”

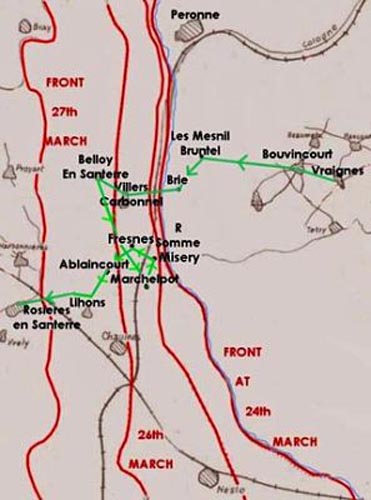

The 26/27th March saw the 150th Composite Battalion withdrawing from Rosieres (Map ref J 9) with one complete platoon of 5th Yorkshires killed or captured.

The 5th Battalion retreat March 1918

Wyrall says in the 50th Division History:

“Thus ended 27th March forever memorable in the annals of the

Division and all units as a day of hard fighting and magnificent courage.”

The end of the German offensive on Amiens saw the 5th Army

in a state of total confusion with Battalions, Brigades and Divisions all

jumbled up, fighting as mixed units under different commanding officers.

By 31st March the 150th Composite Battalion found itself in a line Moreuil

(Map ref H 9 ) to Hangard (Map ref I 9). On 1st April, what remained of

the 150th Brigade marched off to the suburbs of Amien (Map ref G 8). It

was totally exhausted by ten days of constant fighting with no sleep or

proper food and numbered only 849 men of which 234 were 5th Battalion men

including Samuel Maltby. Wyall observes:

“The results of the Great German offensive on the Somme in March

1918 were terribly disappointing to the enemy. That he did not break through

was due to the splendid courage and tenacity of the British soldier. The

fine fighting displayed by ALL units of the 50th Division received but little

notice in official despatches.”

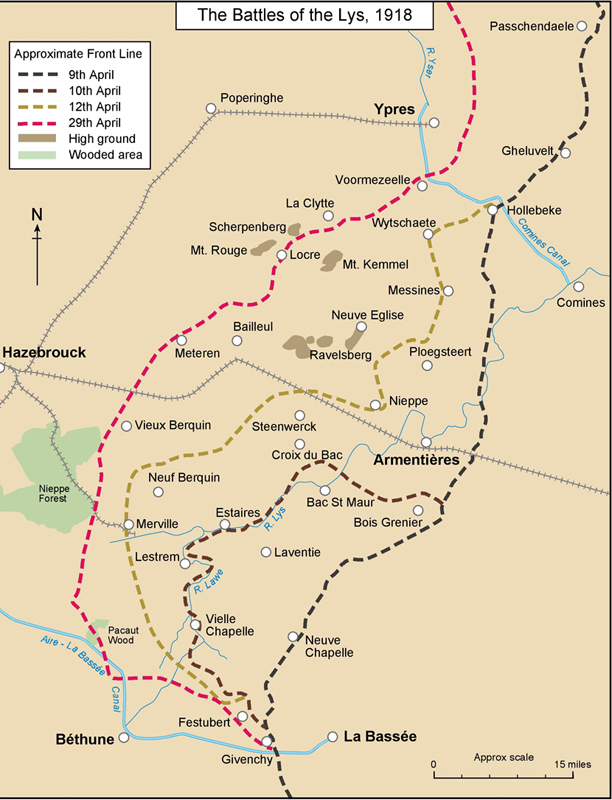

Although the St Michael offensive had failed, the German High Command still thought that they could smash through the BEF in Flanders and gain control of the channel ports. The 50th Division regrouped but did not have time to get its breath back before the next blow. On 9th April they were moved to the North of Bethune (Map ref I 4 ). The 5th Battalion war diary contains the details of the action during 9th to 16th April 1918 in what was officially called the Battle of the River Lys or to the Germans, the Georgette offensive. Their intention was to capture the rail hub of Hazebrouk (Map ref I 3) and then the channel ports of Dunkirk and Calais. History repeated itself for the 150th Brigade as it became split up in the confusion of battle and had to form a weak battalion of stragglers, falling back to the town of Merville. (Map ref I 4).

German offensive on the River Lys, April 1918

Peter Hart, in his book ‘1918, A Very British Victory’

has a quote from Brigadier General Rees Commanding Officer of the 150th

Brigade made on 11th April:

“Up and down the line for the next couple of days this was the

nature of the fighting on the 50th Division front. Desperate men clinging

on as best they could, falling back, filtering in the newly arriving reinforcements

that were inevitably chewed up in the intense fighting.”

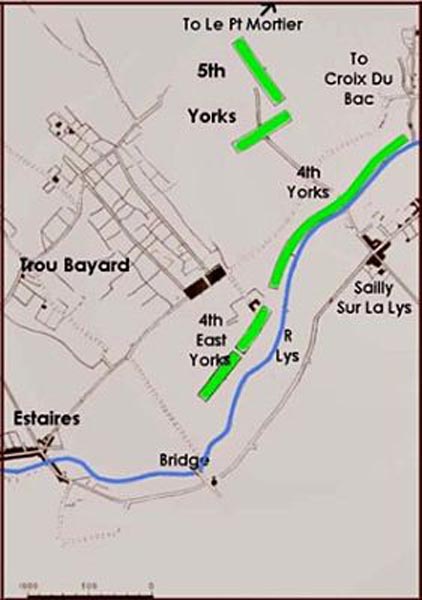

The sector in which the 50th Division men found themselves had been held by Portuguese troops for a long time, and when the German attack came, they gave way in flight. The 50th Division tried to plug the gap and to prevent the enemy from crossing the River Lys at Estaires (Map ref J 4). This they achieved until they withdrew in the dark on 10th April.

4th and 5th Battalions’ defence at Estaires

Wyrall records:

“Large bodies of the enemy attempted to press back the line but

the battalions with fine tenacity stuck to their positions.”

This time the troops of 50th division were mentioned in the

official despatches:

“At Estaires the troops of the 50th Division tired, reduced in

numbers by exceptionally heavy fighting of the previous three weeks and

threatened on their right flank by the enemy’s advance south of the

river Lys were heavily engaged. After holding their position with great

gallantry during the morning they were slowly pressed back in the direction

of Merville.”

On 11th April the situation was even worse as the Division

history reports:

“At 9.5 am 5th Green Howards reported that the enemy pressure

on the front was great. Fighting hard, the Green Howards held on until practically

surrounded. Many were captured and wounded owing to impossibility of getting

away.”

Miraculously some did get away including Samuel Maltby who, given the circumstances, was leading a charmed life. The remnants of the 4th and 5th Battalions went to Doulieu (Map ref J 3) and formed a composite battalion under Lt. Col. Thomson of 5th Battalion Green Howards. The 50th Division had taken another pounding and was relieved on 16th April. As the Regiment History tells us the 5th Battalion had sustained 698 casualties between 22nd March and 12th April.

General Horne of 1st Army wrote on 15th April:

“I appreciate the magnificent way in which the 50th Division have

fought since 9th not only against overwhelming superiority of numbers but

under particularly difficult circumstances.”

The Division had been decimated again and new young recruits

joined the ‘old guard’- one of whom was Samuel Maltby, aged

only 24, who, having survived the two German offensives might have thought

that his life was protected given the very high casualties experienced in

his 5th Battalion. How wrong he would have been if he had imagined that

the worst was over.

Certain units of the BEF had suffered especially badly during the German

offensives of March and April 1918. These were the 8th, 21St 25th and 50th

Divisions. They were relieved by French troops in late April and sent to

the Champagne region to what had been a very quiet part of the front, the

region of the Chemin des Dames, the scene of fierce fighting by the French

Army in 1917. These Divisions came under the direct command of the French

and immediately on arrival went into the front line. The British commanders

protested but the French said that in no way would the Germans be attacking

this sector as they were much more concerned with getting to the channel

ports. The 5th Battalion Green Howards occupied a part of the ridge known

as the Plateau de Californie and continued to train the new recruits.

-----------------> Return to top of the page